Dear Clive,

I noticed your web-site on Chilton Cantelo School and that you are interested in stories from the Capt. Cotes-James era. I have a little story which I think is well worth mentioning. It comes from February 1978, which seems a long time ago now (!), and so I can only tell it as I remember it. The school comes in, heroically, a few paragraphs down, so please bear with me…

In 1978 I was living at No 5 Lower Chilton Cantelo. My husband was an aircrewman based at nearby RNAS Yeovilton. No 5 was one in a row of labourer’s cottages, originally attached to Lower Farm, as far as I know. The older Mr & Mrs Kerton were at Higher Farm, and Cdr Goodford at the old vicarage. The school was run by Capt. James, whom I never saw, but as we locals plodded along the road to Mudford, we were often obliged to step quickly into the muddy edges of the lane to avoid being hit by this posh white car that would come hurtling by at goodness knows what speed. My friend would say, “Oh, that’s Captain Cotes-James, from the school!” And we’d step back into the lane, muttering and somewhat disgruntled, as you can imagine.

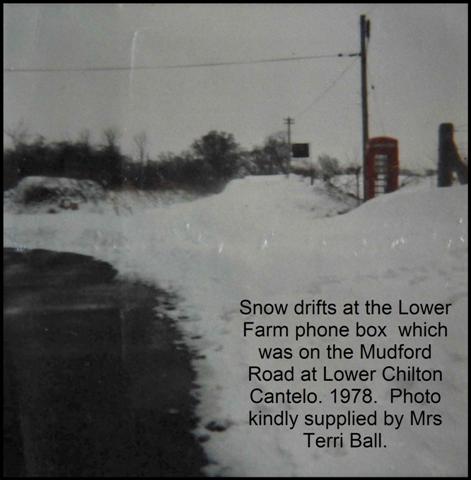

In February 1978 the weather had been cold, but bright and sunny, when suddenly, there was a great change and snow fell thickly, steadily. In 24 hours we had inches of snow, and drifts in the lanes. Thick blizzards continued for several days, sometimes I couldn’t even see Lower Farm House from my window at No 5. I had to dig my way out to the coalshed through a yard that had deeply drifted snow in it. On one side of the lane cars were half-buried. The lanes in and out of the village were filled in with very deep drifts that the men could not walk through. Instead they walked across the fields where the snow was less deep to help the farmer dig his cows out of the field where they were trapped. The farmer at Hinton Farm was Mr Bartlett, and a farmer called Tom Wills had cows in the fields around Lower Farm. They could not send the milk out, so they stored it in bags for a few days and then had to pour it away. Some men from our hamlet managed to get to Mudford, but the little village shop there soon ran out of supplies. Mudford was cut off from Yeovil, and the whole south-west area was declared an emergency area.

At that time my husband was away in the arctic with the Royal Navy, and I was at home with our first baby, just one month old. We were dependent on commercially produced baby-milk powder to feed our baby, and I was extremely worried as we had very little left at home. I had been expecting to go into Yeovil to buy baby milk and groceries. The snow had arrived without warning. The coal-man had also been due to deliver that week, and we were nearly out of fuel. Rob Garrad at No 9 was able to bring unpasteurised milk from the farm, but none of us were very happy about using that, and I was desperately concerned about the health of our baby. There was no telling how long this situation was going to continue. The older locals could not remember anything like it.

I think it was three days into this crisis when two tall young men turned up, astonishingly, on our doorstep. They were freezing cold, despite being clad in very good winter gear, including hats with earflaps and gauntlet-style gloves. (I had heard that the temperature was minus 15 degrees). I asked them to come in, and albeit a bit shy, they did so. They were very pleasant and polite, one dark haired, one fair. How on earth did they get here?! The fair one was the main spokesman. He explained that Captain Cotes-James had organised some of the older boys from the school to go out in pairs to help the locals in the village. In particular there was to be a helicopter-drop of food at the school in the coming days, and they were collecting a list of food items we might need. If we had no money handy to pay now, we could pay the school when things had returned to normal. I requested a few things, which the fair one wrote down, though his hands were so numb he could hardly write. I also wrote a brief note to the Captain explaining my situation with the baby and the urgent need for baby milk-powder. The young men, probably, sixth-formers, set out again into the snow. It had taken them a couple of hours to get this far.

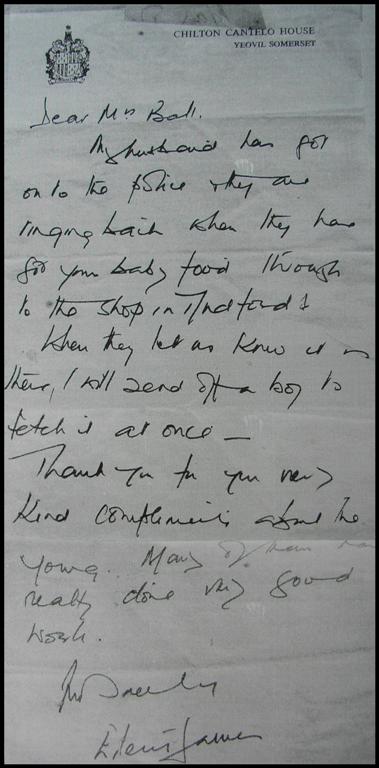

I was still worried, as the continuing snow storms could delay the helicopter delivery. However, a couple of days later the young men returned carrying heavy back-packs, distributing food to those who needed it. They also brought me a note from Mrs Cotes-James.

The helicopter had not brought baby milk but she had phoned the police in Yeovil who would get some for me at a shop in the town. They could not bring their vehicles any nearer than the bridge at Mudford, as very little snow-clearing had been done except for the major roads. So a boy was sent from the school to make his way over the fields and along the riverbank (that’s what I understood at the time) to collect the boxes of baby milk from the police. These he brought to our house at Chilton Cantelo.

I cannot tell you how relieved I was. To me this was a life-saving situation, and these school boys were brave young heroes. About a fortnight later the snow melted and we were cut off by flooded lanes for a short while, but the danger had passed. Things soon returned to normal, and again we locals would be plodding up from Mudford, me pushing a small pram now, and again we would dash for the hedge to avoid the posh white car racing by us. But now I would give the car a grateful and happy wave, and the driver would toot his horn in greeting.

I hope you enjoyed my story, I’m glad to say “Thank You” again to any of those young men, now middle-aged no doubt!, who may recognise themselves in this story.

Yours sincerely,

Mrs. Terri Ball